Crying wolf, again? Another twist in the tale of offshore’s perceived decline

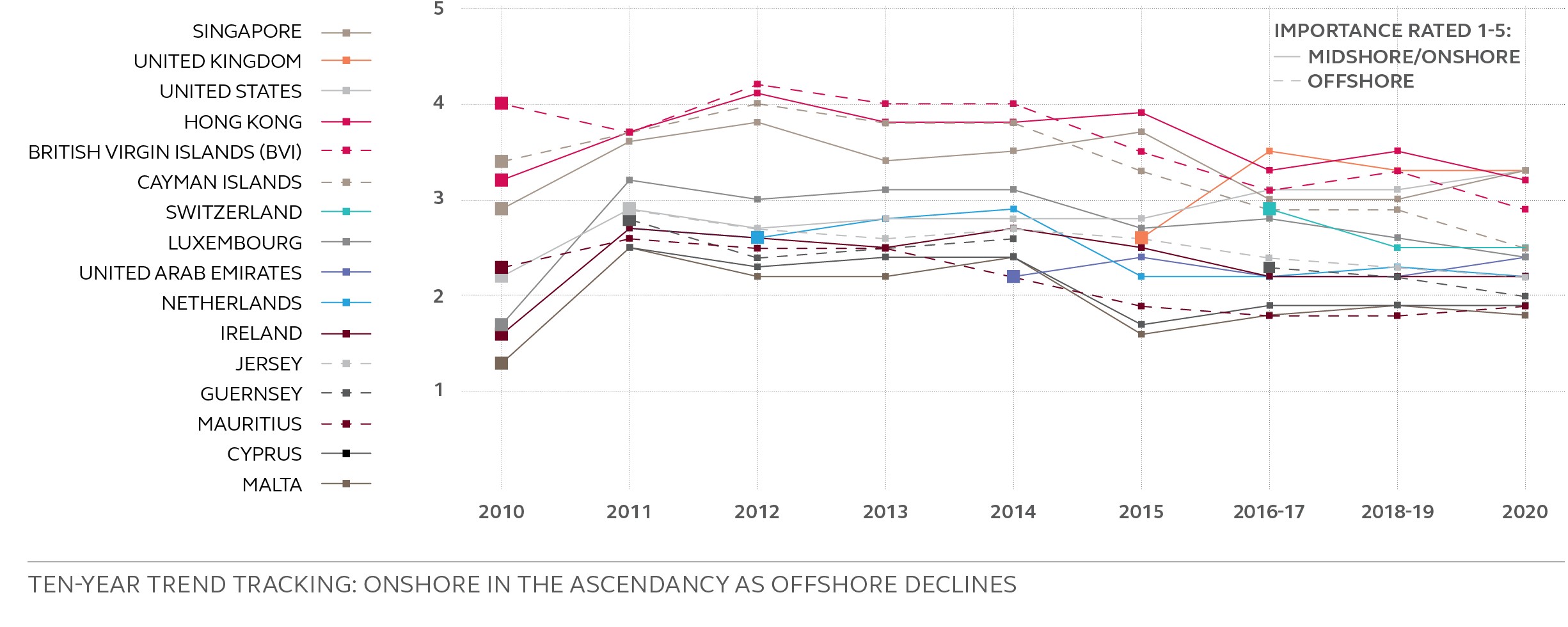

Back in 2010 when Vistra conducted its first annual survey of the corporate services industry, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and the Cayman Islands were ranked as the two most important global jurisdictions by respondents.

Roll the clock forward to 2020, and these two offshore centres sit in fifth and sixth place respectively, while Singapore and Hong Kong have risen above them in the rankings.

This is part of a bigger picture: over the ten years the study has been running, all of the offshore centres in the rankings – including the Channel Islands, Mauritius and the Seychelles – have experienced a net negative change in perceived importance.

Marginal centres feel the squeeze

The competitive challenges facing offshore jurisdictions have grown substantially over recent years.

The proliferation of tax and transparency rules post-global financial crisis has seen the perceived tax planning and privacy benefits of locating in these jurisdictions somewhat diminish. And the related compliance burden has increased the costs of doing business there.

Despite this, as recently as 2018, the BVI still ranked in the top two of Vistra’s global jurisdictions. And, up until 2019, new incorporation volumes in the BVI and Cayman remained strong.

Then, in 2019, came the EU’s economic substance rules, which impact the Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories, among others, by increasing the cost and complexity of incorporating and maintaining corporate vehicles in these jurisdictions.

The upshot has been to further erode some of the cost advantages of incorporating in offshore centres. Three-fifths (59 percent) of Vistra’s survey respondents think the increased cost of doing business will lead to a drop-off in demand. In fact, both the BVI and Cayman saw a fall in new incorporation volumes in 2019, versus 2018, which may be partly attributable to the substance rules coming into effect.

For some of the less strategic island nations, which don’t have the specialist infrastructure and expertise to differentiate themselves, the substance rules could be the final straw. The likes of Samoa and the Seychelles have the added challenge of being put on the EU’s list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes.

The more established jurisdictions, however, such as BVI, Cayman and the Channel Islands, have more cause for optimism about weathering this latest storm with strengths that few midshore or onshore centres can match.

The BVI’s modern and flexible legal structure, strong shareholder protections and high service levels makes it a preferred destination for corporate holding structures. Cayman maintains its position as the world’s leading domicile for alternative funds, with its specialist expertise, flexible regime and willingness to respond quickly to evolving industry needs. While the Channel Islands are largely unmatched in experience in areas such as succession planning and trust administration.

Asia is the key battleground

While BVI and Cayman are two offshore centres that may feel their future is more secure, developments in Asia over the next decade will be critical to their long-term prospects.

Chinese investment drives a huge amount of the incorporation activity in the BVI, and Japan and China together account for a substantial chunk of the estimated US$4 trillion net fund assets domiciled in Cayman.

According to the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority’s 2018 records, Japan is one of only three jurisdictions whose investors hold more than 10 percent in over 1,000 Cayman-registered mutual funds; the others are the US and Cayman itself. Chinese domiciled investors hold this share in 367 Cayman funds, and Hong Kong investors in 732, and these numbers were up 27 percent and 30 percent respectively on the previous year.

Historically, Singapore and Hong Kong haven’t posed a serious competitive threat to Cayman and BVI’s core business areas. In fact, Hong Kong has largely had a complementary relationship, driving business – often originating in China – to the two offshore centres.

More recently, however, Singapore’s government has been working to enhance its competitiveness with Cayman’s fund regime by introducing a new corporate structure, the variable capital company (VCC), which took effect in January. Hong Kong, meanwhile, introduced a bill for a Limited Partnership Fund regime in March, establishing a vehicle designed specifically for the needs of private equity funds.

Given that Asian clients, in particular, have been such major drivers of business for offshore centres over the last decade, their continued loyalty in the face of rising competition will be critical.

How these battles play out in the region will be an important indicator of offshore’s long-term prospects. If these highly specialised centres can maintain their status as preferred destinations for Asian investors over the coming years, versus powerful midshore players that now seem to be challenging them, it will be another sign of their resilience. And the latest wolf to rear its head may prove less formidable than is currently feared.

Find out more about Vistra 2030 and download the report here

The contents of this article are intended for informational purposes only. The article should not be relied on as legal or other professional advice. Neither Vistra Group Holding S.A. nor any of its group companies, subsidiaries or affiliates accept responsibility for any loss occasioned by actions taken or refrained from as a result of reading or otherwise consuming this article. For details, read our Legal and Regulatory notice at: https://www.vistra.com/notices . Copyright © 2024 by Vistra Group Holdings SA. All Rights Reserved.