New UK law targets non-UK corporations in low-tax jurisdictions

Starting April 6, 2019, the UK government will levy a 20 percent tax on income derived from intangible property held by non-UK resident entities located in low-tax jurisdictions. The new rule applies only to income related to the sale of goods or services in the UK.

Essentially, if your multinational organization holds intangible property (i.e., intellectual property) in a no- or low-tax jurisdiction, and this intangible property is used to generate income through sales in the UK, then the royalties from those sales will be subject to the new UK tax. The rule will apply regardless of whether a multinational group has a UK taxable presence.

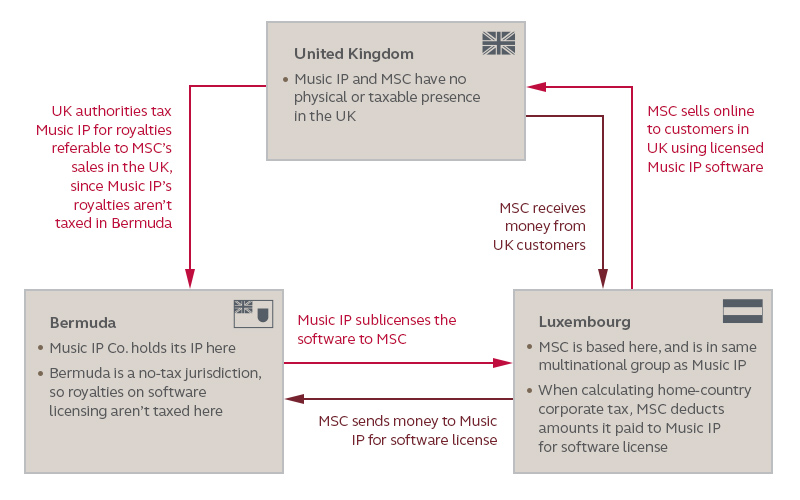

To help clarify when the law will be applied, let’s look at a hypothetical scenario.

- Music IP Co. holds their intangible property (IP) in Bermuda, which charges no corporate tax. Music IP Co.’s most significant IP is a software application that allows users to download music.

- Music IP Co. is not tax resident in the UK and has no physical presence or taxable presence (i.e., permanent establishment) there.

- Music IP Co. provides a licence to sell access to its software to Music Sales Co., known as MSC.

- MSC is based in Luxembourg and is in the same multinational group as Music IP Co.

- Like Music IP Co., MSC is not tax resident in the UK and has no physical presence or taxable presence there.

- MSC sells the right to access and download content online from Music IP Co.’s software to customers in many countries, including customers based in the UK.

- When MSC calculates its home-country corporate tax on sales (including its sales to customers in the UK), it deducts the amounts it has paid to Music IP Co. for software licensing; the amounts are commonly referred to as royalties.

- Because Bermuda is a no-tax jurisdiction, Music IP Co. is not taxed on the royalties it collects from MSC. A portion of these royalties will be related to MSC’s sales in the UK.

- In this scenario, and under the new UK law, the royalties made by Music IP Co. that are referable to sales made by MSC to customers in the UK would be taxed by UK authorities at a rate of 20 percent. (As we’ll see, there are exemptions to this.)

Exemptions under the UK’s new tax rule

The new tax rule applies — at least initially — to entities that hold their intangible property in jurisdictions that do not have a tax treaty with the UK (that is, a double tax agreement with a non-discrimination provision). The UK’s policy paper on the new measure specifies that the tax will apply only “to the proportion of the foreign resident entity’s intangible property income that is referable to the sale of goods or services in the UK and made via both related and unrelated parties.” On a strict interpretative reading of the provisions, then, the new law may apply to the receipt of royalties from a third party.

A foreign entity is exempt from the tax if it pays foreign tax at a rate of at least 50 percent of the UK income tax that would otherwise be due under the new rules. This will exempt those foreign entities that are not holding their IP in low- or no-tax jurisdictions. A foreign entity is also exempt from the tax if its annual sales in the UK are below 10 million pounds.

Multinationals should of course fully understand the new measure’s provisions, and how they relate to their own situations, before relying on any of its exemptions.

Tax collection under the new rule

Given that the new rule applies to companies based outside the UK, the question arises as to how the UK will assess and collect the tax. In response, the rule contains joint and several liability provisions that grant UK authorities the power to collect the tax from other entities in the same controlled group. In other words, any UK-based entities operating in the same accounting group as the foreign entity will be liable for any uncollected tax under the new law.

Those multinational groups that have no UK entities will be under less direct pressure to comply with the new measure. However, those groups must weigh the risk of noncompliance with the possibility that they may want to establish a UK entity or operations in the future. If they did take those actions, they could attract tax collection from UK authorities for past-due amounts, along with any related penalties.

Putting the UK rule in a global context

The UK’s new measure related to offshore receipts of intangible property is another example of tax authorities in a single country implementing a law that’s generally aligned with the OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting program, or BEPS. The BEPS program and related tax laws push corporate groups towards paying taxes in jurisdictions where they create economic value and away from strategies that artificially shift profits to achieve tax advantages.

BEPS-related measures have significantly increased tax risks and burdens for multinationals. Because these measures span literally dozens of countries — over 100 countries have committed to implementing four BEPS minimum standards — it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that each country’s laws remain unique. The UK’s new law is a prime example. The UK has (understandably) implemented a law that specifically targets UK tax avoidance.

In other words, despite OECD efforts to address corporate profit shifting on a global scale — and despite the more than 100 jurisdictions that have committed to implementing BEPS standards — there is no international tax framework. Rather, a piecemeal system of country-specific corporate tax laws remains. The steep challenge for today’s multinational is to keep abreast of these changing laws, and to assess whether the organization’s current, proposed or even possible future group structure and tax arrangements may be affected by them.

The contents of this article are intended for informational purposes only. The article should not be relied on as legal or other professional advice. Neither Vistra Group Holding S.A. nor any of its group companies, subsidiaries or affiliates accept responsibility for any loss occasioned by actions taken or refrained from as a result of reading or otherwise consuming this article. For details, read our Legal and Regulatory notice at: https://www.vistra.com/notices . Copyright © 2024 by Vistra Group Holdings SA. All Rights Reserved.